Interview with Justine Malle

« My father liked to change his identity. »

PostED ON OCTOBER 17 2022

The Lumière Film Festival offers movie fans a chance to delve into the work of Louis Malle through a wide-ranging retrospective of seventeen films, thirteen of which are slated for theatrical re-release, first on November 9th, and then in the summer of 2023, in brilliantly restored versions. Justine Malle, the filmmaker's daughter, revisits the career of her father, who never ceased to renew himself through contact with the 7th Art.

How did Louis Malle enter the wide world of cinema?

His enthusiasm for the cinema appeared quite early. I can't say exactly at what age, but Roger Leenhardt's ‘The Last Vacation’ (1948) caught his attention. This feature film, which deals with the end of childhood, greatly touched him, and when you see it, the connection is obvious. My grandmother was the heiress of the Beghin sugar factory, and she had great hopes that he would take over the business, to the point that when he told her he wanted to make films, she slapped him in the face! This gesture, if I am to believe what he told me, made him even more determined to break into the field.

Yet he grew up far removed from the cinema. My grandparents were highly cultivated industrialists who placed an importance on culture, but I don't think movies were particularly important. My grandmother was very sceptical about my father's enthusiasm for the cinema, according to her letters, and she was convinced it was a temporary phase. She followed his first forays into filmmaking from a distance. Then she was forced to accept it.

What about his father?

When he spoke about him, which was rare, he mainly described him as an absent father. He didn't see him during the war because he had been sent to Thumeries, up north, while the family lived in Paris. He was a rather quiet and guarded person. The two of them did not really see each other. The bright light of the family was his mother. She was a very energetic and religious woman. She didn't take it well that her children were not religious.

Lacombe Lucien, 1974

First, there was Jacques-Yves Cousteau, who launched Louis Malle’s career at the age of 23 with ‘The Silent World’ (1955). The documentary won the Palme d'Or and the Oscar for best film. What a debut!

He was very affected by this phase, which was very formative because it gave him a technical background and developed his relationship with the documentary. It also deeply nurtured his imagination because, with Jacques-Yves Cousteau, they travelled extensively. This experience instilled in him the idea that nature is a preserved world, and it fuelled a nostalgia for a lost paradise. In ‘Phantom India’ (1969), he talks about his nostalgia for the Seychelles. He had a very good relationship with Jacques-Yves Cousteau. He jumped at the chance to work with him!

Another great filmmaker also seems to have had a huge impact: Robert Bresson. Louis Malle participated in the preparation of ‘A Man Escaped’. What effect did this experience have on him?

Robert Bresson was a truly great filmmaker in his eyes, without a doubt. For my father, ‘Pickpocket’ (1959) was the absolute masterpiece. When I saw the film at age fifteen, it was a shock and I never spoke to him about it, thinking that it wasn't necessarily his type of movie. However, years later, I came across an article in which he said that this film had been an instigator for him. He didn't talk much about his past films and cinema in general. His cinephilia was something quite intimate. He was not someone who was interested in passing things on.

Two years later, he made his first feature film, ‘Elevator to the Gallows/Frantic’ (1957), with Jeanne Moreau in the cast and Miles Davis on the soundtrack. And he won the Louis Delluc prize...

At the risk of disappointing you, I don't think ‘Elevator to the Gallows/Frantic’ was a film that was particularly close to his heart, unlike ‘Phantom India’ (1969) and ‘Lacombe, Lucien’ (1974), a feature film that he developed over a long period of time. He didn't want to start with something personal, but rather with a genre film. It was almost a strategy on his part. For my little sister and myself, his precocious side was a bit overwhelming, not to say intimidating and difficult to bear. When I discovered ‘Elevator to the Gallows/Frantic’ as a child, I remember finding it a bit dated. Personally, I don't have any particular affection for that film. I tend to think it's a feature film that overwhelms others, even though it is obviously very good. It's a bit like ‘Goodbye, Children/Au Revoir les enfants’ (1987): I regret that these movies are like two trees that hide the forest. He directed other films that are more like him. I feel a kind of sadness in thinking that we are most often talking about these two feature films, yet he is someone who had advanced all his life, who had further deepened his art.

When ‘Elevator to the Gallows/Frantic’ was released in theatres, French cinema was just at the dawn of the New Wave. What did he share with this movement and how did he differ from it?

Although the critics put him on the fringe of the New Wave, and invented conflicts between him and some of its members, my father was undoubtedly an integral part of it, from a technical point of view. He was good friends with François Truffaut and often joked that he was one of the precursors of the movement with ‘Elevator to the Gallows/Frantic’. However, I don't think he thought of his first movies with the idea of being part of this movement because he didn't like being labelled. He didn't disassociate himself from it, but he didn't want to belong to it completely either.

In terms of form, he tried his hand at many genres: film noir, adaptations of books or plays, documentaries, and he sometimes mixed them too, such as the Western comedy Viva Maria! (1965). But one thing remained constant: he held a very acerbic view of the political world and the bourgeoisie. Why?

He was outraged by injustice and the fact that he was born into a very bourgeois, very privileged environment gave him a feeling of legitimacy to talk about it. He felt he was well-placed to judge it. The injustice he recounts in ‘Goodbye, Children/Au Revoir les enfants’ [the arrival of the Gestapo in a school to arrest three Jewish children] marked the beginning of his indignation. He was very critical of his environment for many biographical reasons. He had a clear vision on this issue.

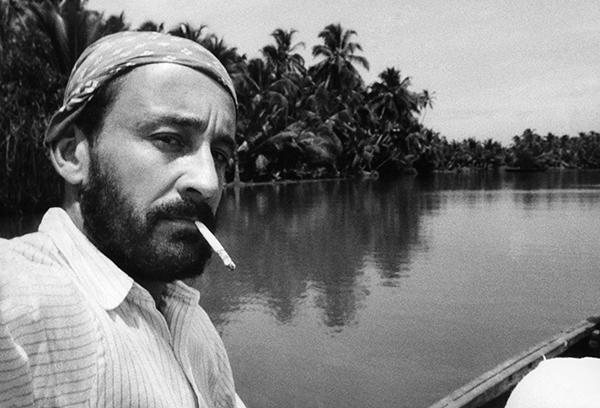

Louis Malle on the set of Calcutta, 1969

In 1971, he directed ‘Murmur of the Heart’, which deals with incest, and three years later, ‘Lacombe, Lucien’, which evokes wartime collaboration. These two films caused controversy and he was accused of having a lack of moral judgement, which led to his exile to the United States...

The lack of moral judgement that he has been accused of is a misunderstanding. It is even a misconception, to which he may also have contributed by adopting a somewhat dandyish or cynical posture, but it was not at all in contradiction with his strong awareness of good and bad. In fact, from my point of view, it is very present in these two films. He doesn't make judgements, but lets the viewer arrive at them alone. He didn't want to be a beautiful soul: he was someone who had a very solid moral compass. I saw this in my daily life.

With ‘Goodbye, Children/Au Revoir les enfants’, he made a remarkable comeback in France, dealing with a very personal subject...

And yet, at the beginning, nobody wanted the movie. It's a feature film that wasn't easy to make because everyone was a bit sceptical. The success it achieved was therefore a real surprise. You should also know that my father had never evoked this very intimate story. I didn't know that he had experienced this event. He carried this story with him for a long time and I don't know why he chose this moment to direct it. In ‘Goodbye, Children/Au Revoir les enfants’, I discovered what my father’s life was like when he was twelve.

Between his exile and his return to France, there was what is known as his ‘American period’. Was going to the United States a way of wiping the slate clean?

He was someone who liked to change his identity and who hated being confined to one place. When he decided to go to India, it was because he realised, particularly during the shooting of ‘The Thief of Paris’ (1967), that he was unable to reinvent himself. Going to the United States was a way for him to escape his social environment and start anew. He felt very judged and constantly drawn into himself. He suffered a a great deal because he was in a state of revolt against his background and legacy. So there is indeed this idea of making a clean sweep, even if he didn't become a Trotskyite either! It is also for this reason that the timing of this retrospective is perfect: nobody knows what Beghin Sugar is today.

What kind of filmmaker was Louis Malle on set? How did he direct his actors, for instance?

He had a lot of respect for them because he felt they were the only ones who exposed themselves and put themselves in danger in the cinema. My father was passionate about human beings and, by extension, about actors. He often joked that he used to film fish and that it was much easier! It took him some time to find a link with them. This connection with the actors is something in depth that he worked very hard on. He did not use psychology for the roles, and on set, he simply gave indications of rhythm. I knew from technical-specialist friends that he was a director who was always very concentrated, who was constantly looking for the truth. He was very anxious and had the perpetual impression that everything was going to go wrong. One has this image of a man who succeeded in everything, but he was above all a very anxious person.

What do you think his legacy is in contemporary cinema?

There is always the impression that his cinema mattered to no one. And yet, when you dig deeper, you realise that it is each of his movies, taken independently, and not his work as a whole that made a mark. Bertrand Mandico, for example, is an absolute fan of ‘Black Moon’ (1975). It's an unlikely choice if you think about it! For Arnaud Despleschin, ‘Vania on 42nd Street’ (1994) is a cult classic. My father’s relationship to childhood also greatly influenced Wes Anderson. His legacy is perhaps most evident in the way he films childhood. He is not someone who theorised cinema. He could have, because he was intellectually refined, but he preferred to be hands-on.

How do you feel about the re-release of part of your father's filmography in movie theatres?

I am delighted! Every time I saw his movies again, I’d say to myself that it was a real shame that people didn't see them in the cinema. ‘The Thief of Paris’ (1967), for example, is a must-see feature film. I am also glad that these re-releases are not happening in a random way, but in groups.

The Thief of Paris, 1967

Interview by Benoit PAVAN

Screenings of the day:

Murmur of the Heart by Louis Malle (Le Souffle au cœur, 1h59)

> CINÉMA COMŒDIA 10:45am

In the presence of Alexandra Stewart and Benoît Ferreux

The Fire Within by Louis Malle (Le Feu follet, 1h49)

> PATHÉ BELLECOUR (THEATRE 1) 1:30pm

In the presence of Alexandra Stewart

The Lovers by Louis Malle (Les Amants, 1h31)

> PATHÉ BELLECOUR (THEATRE 1) 4pm

In the presence of Justine Malle

Elevator to the Gallows/Frantic by Louis Malle (Ascenseur pour l'échafaud, 1h33)

> UGC CINÉ CITÉ CONFLUENCE (THEATRE 2) 11:15am

In the presence of Olivier Barrot (journalist, author)

Black Moon by Louis Malle (1h41)

> UGC CINÉ CITÉ CONFLUENCE (THEATRE 2) 4:45pm

In the presence of Alexandra Stewart

Zazie dans le métro by Louis Malle (1h33)

> LUMIÈRE TERREAUX 11am

In the presence of Justine Malle

May Fools by Louis Malle (Milou en mai, 1h47)

> CINÉMA BELLECOMBE 8pm

In the presence of Justine Malle

Lacombe, Lucien by Louis Malle (Lacombe Lucien, 2h18)

> CINÉ'MIONS / MIONS 8pm

In the presence of Eric Guirado